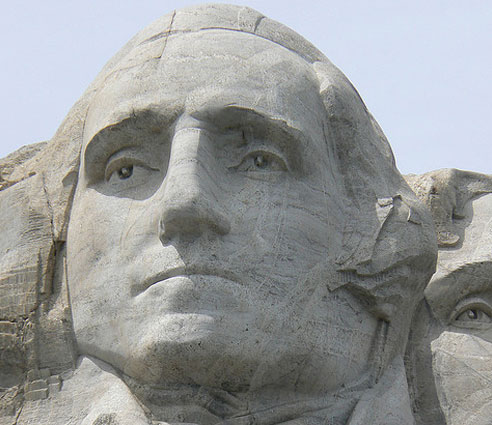

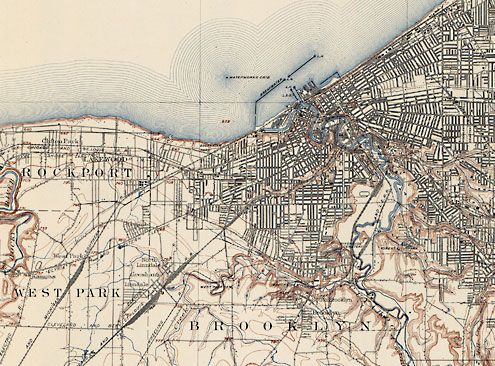

Creating topographical maps that represent the lay of the land used to be a painstaking process that took years of travel and further hours of pouring over collected data. The resulting map, while functional, paints a distorted representation of the actual lay of the land. This baseline understanding of a landmass unlocks the history of its changing terrain and inhabitants, but to a fault. On Rapa Nui, or Easter Island, where questions about its many statues remain unanswered, the shortcomings of old techniques fly in the face of today’s archaeologist.

Advanced Mapping

Modern topography goes beyond the simple record of elevation and land features. Today’s language around the subject concerns geospatial data sets. These comprehensive feeds are the result of thorough research collected using updated techniques such as the near-infrared sensors and the orthophoto. Unlike a typical aerial photograph, the orthophoto accurately depicts a photographic map. Where aerial photos cannot account for tilted shots that create image displacements, an orthophoto creates a uniform scale. The difference between the two may be nearly imperceptible to the human eye, but the photographic map’s value to the researcher leads to more complete data.

Unmanned and Unexpected

Unlike more populated parts of the Earth, Rapa Nui lacks a comprehensive geospatial data set. All known data collected by the human eye answers no questions about the history and reasoning behind the island or its iconic statues. A team of researchers from California State University Long Beach, led by professor of anthropology Carl Lipo, decided to approach this problem using commercial technology known as an unmanned aircraft system.

Unlike the popular quadcopter drones owned by private citizens, the UAS resembles a full-sized airplane. Equipped with a camera and controlled by a computer on the ground, the unmanned unit follows specific flight plans that allow for a much bigger picture with unsullied, inclusive data.

Lipo and his team used the UAS over the course of nine days to cover a section of Rapa Nui. Over the course of 26 missions, the team captured 26 different orthophotos and made strides in topographical and hydrological data. They reported immediate results and observed unique insights based on this data. Lipo reported that, based on the information they gathered, Easter Island’s ancient culture positioned its statues to signify nearby water and not for visibility as previously assumed. The UAS performed so well that CSULB decided to continue covering the entire island in future projects.